At Shaamazi, we created and open-sourced our logger: antilog. We created this out of frustration at the other loggers available for Go. In our minds, they all fell short in at least one of several ways. We wanted a logger that was simple and easy to use. A logger that doesn't bring a mountain of dependencies. A logger that outputs structured logs. A logger where context can be built over time. And finally, a logger that doesn't have log-levels.

Here I'll look at the following:

- Why we care about logging so much.

- What the current logging landscape for Go looks like.

- Why each of these fundamental features (structured logging, building context and no log-levels) are so important

- How popular alternatives fail to meet our needs.

Why we care about logging so much

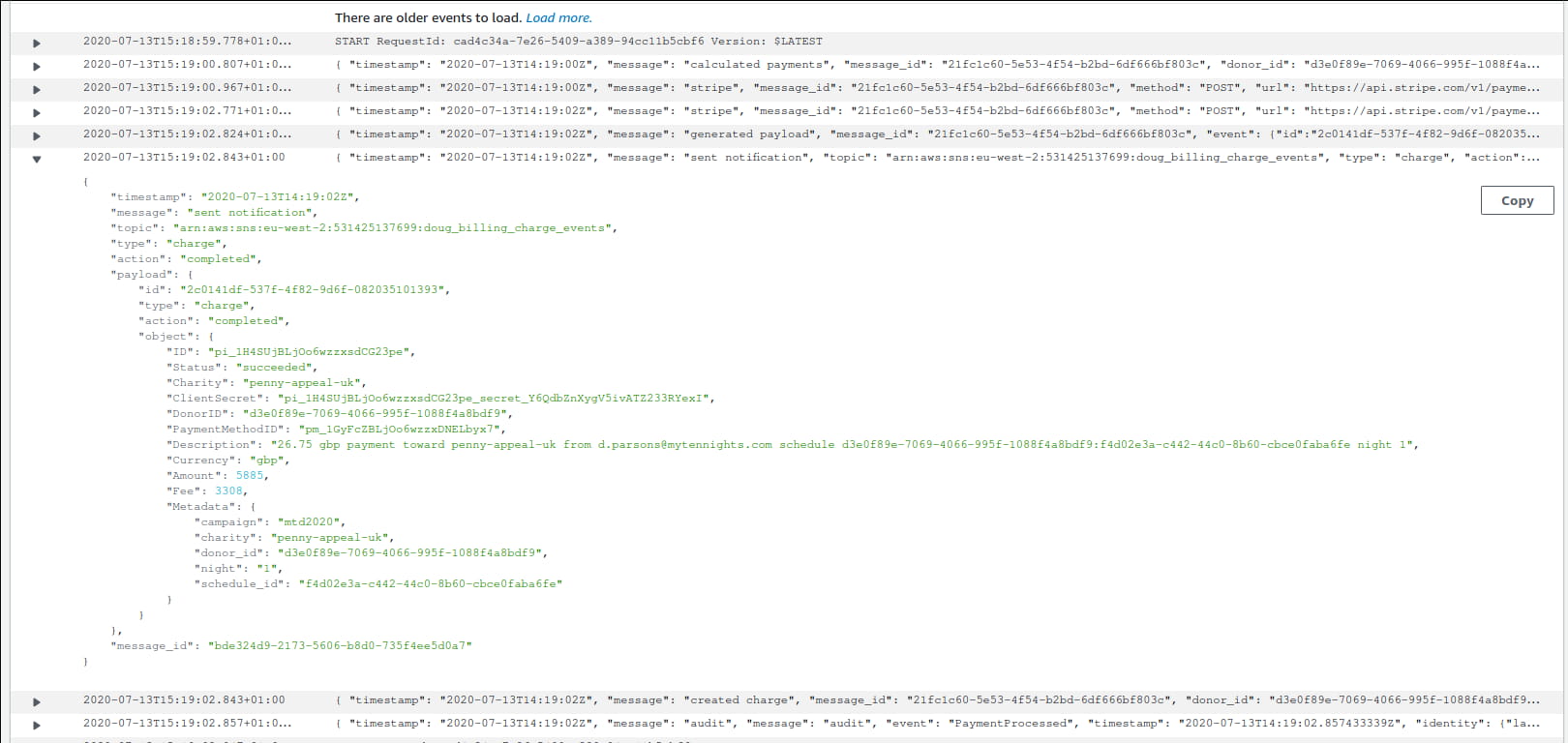

Our largest product is a charity system that automates donations during Ramadan. Over 160,000 people, in around 140 different countries, use this product. Despite this, our engineering team is tiny with two engineers working on this product. As a result, the ability to quickly and efficiently identify problems in our code through inspecting logs is crucial.

What other logs are there?

Go's standard library provides a logger module. Yet, this module is very minimal: it gives a series of functions that can be called to log text, but little else. There are some 'batteries included' logging frameworks, such as logrus. Unfortunately, we wanted a middle ground between the two. Logrus provided too much customisability. It is very verbose to use, and has a significant footprint. However, the standard library wasn't able to provide all the features we wanted. A third alternative is the zap logger created by Uber. This looks like a strong contender but adds a lot of complexity. It has far more configuration with its various logger types (Sugar, Production, Development, etc.). There is also a Sync() function, a mix of sprintf and structured logging, and log-levels.

Other alternatives do exist, but we could not find one that met our criteria.

Structured Logging

Structured logging is the idea that logs should be more than a string message. They should also be able to embed and display structured information. There are two approaches to this: using a human-readable logfmt format, or, writing logs out as JSON. Logfmt has it's advantages; it is arguably more human-readable at an initial glance. However, most tools for searching through logs, such as Splunk, Kibana or CloudWatch, provide support for JSON logs. JSON is easier for programs to read and query and also allows complex datatypes to be expressed in logs. In our case, we are writing logs into CloudWatch. CloudWatch provides explicit support for querying JSON logs. As a result, we are only interested in writing JSON.

The ideal would be for any logger to output JSON by default. Some loggers, such as zap, meet this need. Of the main two most popular contenders, the standard library and logrus, both fall short. The standard library doesn't provide structured logging at all. Logrus does but requires some small amount of config to achieve this (logrus.SetFormatter(&logrus.JSONFormatter{})). This configuration is only a single line of code, but it is easy to miss when writing a new application, script or tool.

Supporting many output formats is another pitfall. This adds more complexity to the logger, making it bulkier than we would like (in both binary size and CPU time). Instead, a logger that outputs JSON by default with no configuration required is ideal. antilog can be used straight out of the box, it requires no configuration at all.

Building Context

As part of our logging, we want the ability to build up of information in logs over the lifecycle of an operation. To get a full picture of what is happening in our logs, we need to be able to provide context to any messages. To illustrate this point, here is a pretty rubbish log message that could show an issue parsing data:

{ "timestamp": "2019-11-18T14:00:32Z", "message": "unable to parse json" }

We can't easily identify what is going on here: is this an application issue? is it expected? What's causing it? By adding a small amount of context we can immediately glean much more information from our logs:

{ "timestamp": "2019-11-18T14:00:32Z", "message": "unable to parse json", "path": "/api/signup", "method": "POST", "status": 400, "request_id": "1234abc"}

We can now see that it's an API endpoint for signup this happened at. From the 400 response, we can assume that this is due to a user submitting bad data rather than an error in our system. From a small amount of context, a previously meaningless log message becomes valuable.

Unless we have a messy codebase, the places where want to write logs don't necessarily have access to all the information we might want. We don't want polluting to our code by passing path, method, request_id and many other fields around. We want the ability to attach these to our logger, building up the eventual output one piece at a time.

In antilog we can build up an output by passing the logger around (or attaching it to context, if you've done much Go):

logger := antilog.With(

"common", "this is a common field",

"other", "I also should be logged always")

logger.Write("I'll be logged with common and other field")

logger.Write("Me too")

No Log levels

A lack of log-levels seems like an oversight for a logging library. However, I strongly believe they aren't necessary and just complicate matters. Dave Cheney argues the same on his blog. This can be broken down by reasoning about each different log level:

Warning:

Warning messages fall into one of two categories:

- warnings you can ignore

- warnings you can't ignore

Warnings that you can ignore are interesting. By definition, nothing has gone wrong. As such, they are no different to info level logs. Warnings that you can't ignore show the opposite: they are errors that are not logged at the correct level. As it is impossible to have a warning that does not fit into these two categories, warning as a log level is useless.

Error:

A similar approach removes the need for errors. Errors fall into one of two categories:

- Errors that you are handling (and recovering from)

- Errors that you are not handling.

If you are handling the error, then the application will continue as expected, and the log line is only informational. If you are not handling the error, then you should not be logging it. It is the responsibility of the calling code to manage this error. As it is impossible to have an error that does not fit into these categories, the error log level is also useless.

Info:

Now there are no more warnings and errors, we have a single log-level: info. By itself, this is no different to not having any log levels at all. Instead, we have 'things we should log' and 'things we shouldn't log'.

This argument to remove log levels can extend further. Log-levels are an attempt to provide a measure of how useful a particular message is. This is a flawed approach as the usefulness can't be determined when the message is written. This is because we do not know why our future selves may be looking at logs. It could be to diagnose a particular race condition, to fix a bug, or to track user behaviour. Without knowing why we will be looking at logs, it is impossible to determine what information is going to be the most relevant. Any attempt to predict is just noise. As a result, log-levels are a fruitless task.

In the context of antilog, we wanted to avoid the typical log.Info, log.Warn and log.Error interfaces most loggers use. This leads to forced decision-making that is not productive. I've been on the end of one-too-many arguments over whether a log should be Info or Warn (see also bikeshedding). Most logging libraries do not give this freedom of thinking, and instead, force you to decide. We, contrastingly, provide just a Write method. Either Write your logs or don't.

In Conclusion

The current logging landscape for Go was lacking. Existing libraries overcomplicated the process of writing logs by falling into one of four traps:

- forcing the use of log-levels;

- lacking structured logging;

- not allowing context to be built

- and allowing too much configuration.

We sought a solution to these problems by creating our logging library, antilog. We've been using it for around a year now and love it.